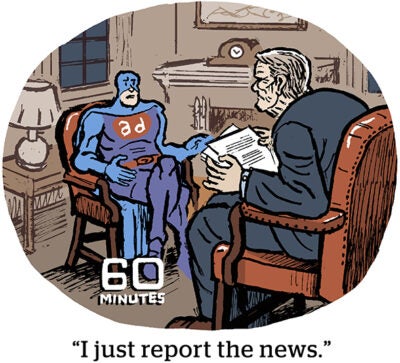

YouTube is in the midst of an ad fraud scandal. As advertisers and agencies struggle to deal with the fallout, a popular piece of advice has been to treat YouTube as if it were TV.

But that reveals another issue: YouTube is now a rival to TV networks.

Yet many networks still post their content to the platform via friendly licensing agreements. In the current war for viewer attention, this is a potentially crippling move.

Back in 2007, I negotiated a deal between the NBA and YouTube that created an official NBA channel on the YouTube website. The value exchange and nature of the licensing agreement was simple.

In return for uploading short clips, such as highlights and best plays, YouTube would promote this official and premium content across the site. Other flagship content owners and networks such as CBS or Discovery made similar agreements.

While there was a revenue component (i.e., the NBA would receive a small share of the ad inventory sold by YouTube), it was an entirely moot point. After all, back then, monetization across YouTube was expressed in thousands of dollars, not today’s billions.

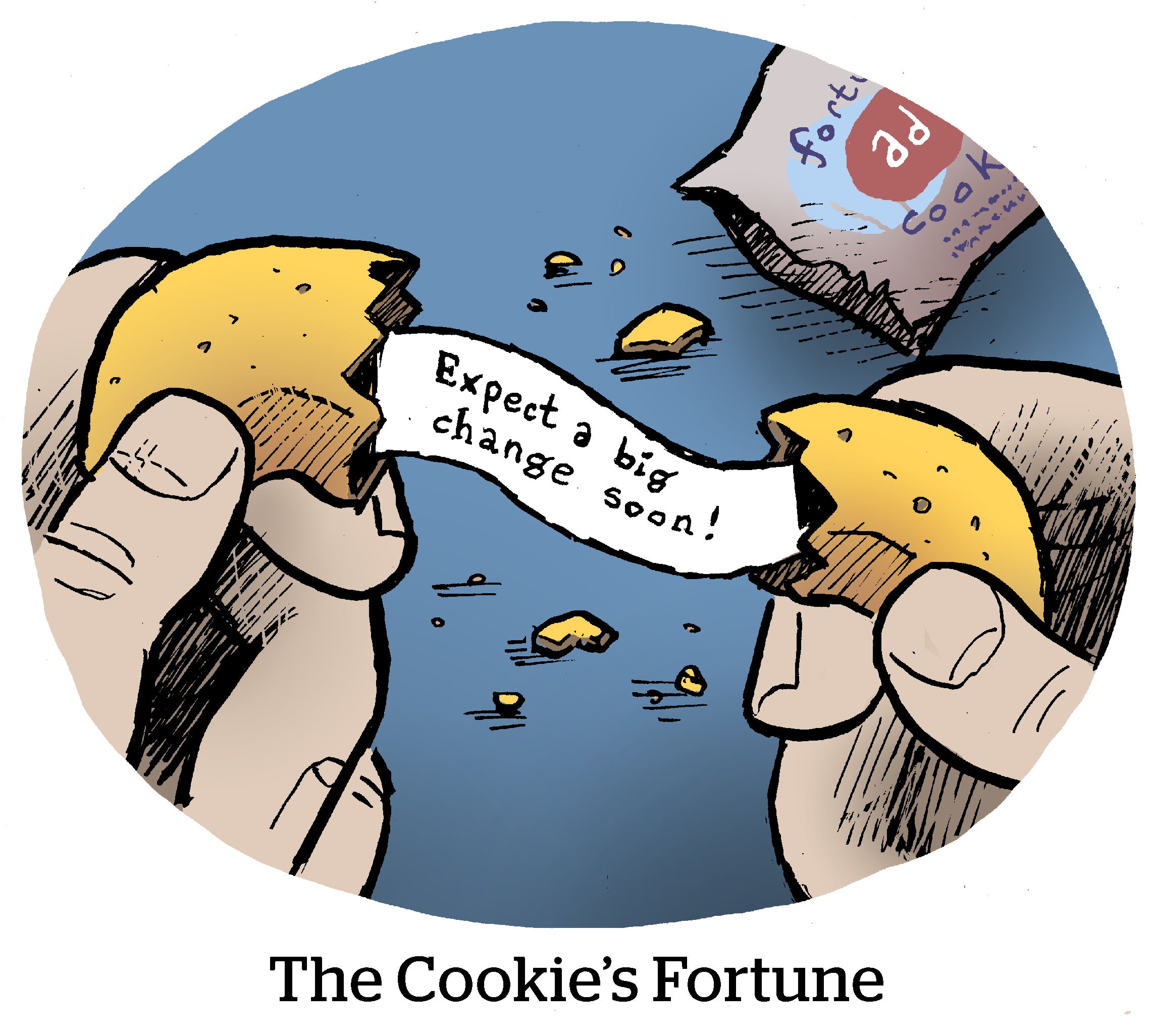

But things have changed since 2007.

YouTube’s new status

YouTube (and to be precise, YouTube.com, not YouTube TV as a virtual MSO) has since evolved beyond promotional shorts and silly cat videos. Today, we can find quality long-form videos and user-generated content (UGC) with a production quality comparable to traditional networks and studios.

Premier League fans (like me) can enjoy 10- to 20-minute NBCU highlights on YouTube. These carefully edited promotional videos have become almost as good as the game itself (e.g., a foul that eventually leads to a goal minutes later will be smartly woven in to give viewers the complete story of the game).

Given the professional-grade quality of YouTube content, it’s no wonder that, over the last 15 years, YouTube viewership has shifted away from the website to a whopping 40% (and growing) now occurring on the big screen.

YouTube has conquered the living room environment that once belonged to the networks. The cherry on the cake is Google’s recent exclusivity over NFL Sunday Ticket.

Networks, for their part, have evolved, too. Each has launched their own streaming service: Paramount+ (by CBS), Disney+, Peacock (by NBCU), MAX (Warner Media Discovery). And these services are widely accessible, either through TV OEMs (e.g., Roku and VIZIO) or bundled with other services (e.g., Peacock comes with Xfinity internet access, and Paramount+ is now part of the Walmart+ bundle).

Networks already hold the millions of so-called “online viewers” that they were once competing for with YouTube. These streaming platforms stand for more than just piping content via IP technology; they hold full monetization capabilities. Hulu, for example, is projected to rake in nearly $5 billion in ad revenue this year.

A tough decision for networks

Given YouTube’s evolving role in the streaming landscape, licensing agreements between networks and YouTube directly undermine the long-term strategy of every streaming service.

Exclusive and original content has been the cornerstone of the SVOD value proposition. Licensing content to YouTube fragments the audience for that content, allowing YouTube to monetize the same people during all the engagement that happens outside the core viewing experience.

The licensing agreements are even less tenable given the recent turn toward AVOD (ad-supported video-on-demand). While NBCU holds the Premier League rights, fans get to see everything they want and need on YouTube instead.

The counter is clear and bold: Networks should back out of their YouTube agreements and focus on their own streaming platforms.

For example, NBCU should make fans watch Premier League highlights on Peacock, rather than on YouTube.

By not licensing content to YouTube, the networks can maintain more control over content distribution. This holds numerous advantages: an ability to better manage the user experience, capture and use customer data, drive stronger monetization and cross-promote other content.

Having built their own robust streaming platforms, and having made deep investments in original and exclusive content, networks can offer an end-user experience that will match (and eventually exceed) what YouTube has to offer.

But even more compelling for networks should be the risk of what happens if they don’t change course. Most of them know about the deleterious impact that Facebook and Google dependence have had over their strategic position – appropriating their audience, siphoning their revenues and controlling their distribution through algorithm changes. They can’t afford to let the same happen with streaming.

YouTube is no longer simply a promotional channel; it’s a fierce rival to the large networks, and it deserves a taste of its own medicine.

It’s time for networks to cut YouTube. Their future depends on it.

“On TV & Video” is a column exploring opportunities and challenges in advanced TV and video.

Follow Tatari and AdExchanger on LinkedIn.

For more articles featuring Philip Inghelbrecht, click here.