Advertisers have relied on IP addresses as a foundational signal for ad targeting and attribution on connected TV for well over a decade.

But, sometimes, foundations crumble.

IP addresses are considered to be personal information under numerous privacy laws, including in Europe, California and Virginia. And as additional US states enact their own privacy laws – we’re up to 11 now, with more on the way – it could get a lot harder to use IP addresses for targeting and measuring streaming ads.

That said, unlike third-party cookies, the IP address isn’t on the brink of obsolescence.

Every internet-connected device, from smart toasters to smart TVs, has an IP address, without which it couldn’t connect to the internet or communicate with other devices on the same network.

“I don’t see a world where [IP addresses are] regulated out of use,” said Anthony Katsur, CEO of IAB Tech Lab.

Still, advertisers and publishers must prepare for restrictions.

As seen in CTV

CTV advertisers glommed onto the IP address as an identifier because it can link devices in the same household. Every device using the same Wi-Fi has an overlapping IP address.

For that reason, “IP addresses are still the most commonly used identifier or linkage point between different data sets in the CTV space,” said Jon Watts, managing director of the Coalition for Innovative Media Measurement.

Household IP addresses only change when network access is interrupted, like if someone reboots their router, which usually doesn’t happen more than every three to six months.

That’s infrequent enough for advertisers to use an IP address as a semi-persistent household ID, Katsur said.

Advertisers use IP addresses for retargeting devices in the same household, such as targeting a mobile display ad to someone who has already seen that ad on TV. They’re also essential for attribution, which has historically been tricky on TV. (Despite recent investments in shoppable TV, most people don’t make purchases directly on their smart TV.)

When the use of IP addresses is restricted for any reason, “campaign efficiency and advertising demand for that inventory drops significantly because direct targeting and attribution isn’t possible,” said Vikrant Mathur, co-founder of streaming publisher Future Today.

The privacy crosshairs

This overreliance on IP address begs the question: What happens if privacy regulators start taking action?

The ad industry’s answer to that question so far has been to look for loopholes.

For example, “deidentified or aggregate data” doesn’t count as personal information under either the CCPA or the CPRA in California.

And so CTV publishers have started to decouple IP addresses from other types of data, such as ad IDs that reveal where an ad actually ran, and/or to only share IP addresses in aggregate.

But for CTV targeting and measurement, the value of an IP address comes from its ability to link different devices in the same household – and that’s already becoming more difficult.

Apple started obfuscating them in the Safari browser in 2021 and, as of this summer, Google no longer logs or stores individual IP address information in Google Analytics 4.

Google also doesn’t store IP addresses to use for personalized advertising on YouTube.

Instead, it reports “anonymized geolocation information in aggregate to help advertisers understand which city, state or country their ads appeared in,” a Google spokesperson told AdExchanger. “The IP address itself is not used in our models and is never tied back to an individual user.”

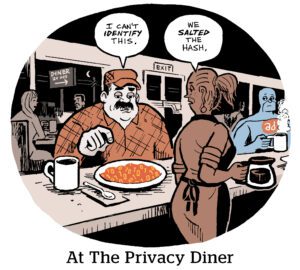

Muddying the waters

All of this uncertainty (and inconsistency) sure is confusing for advertisers.

Privacy regulations have had a “major impact” on how publishers and ad platforms decide to share (or not share) data, said Mike McCarver, SVP of data and programmatic at Horizon Media.

For example, Horizon Media was accustomed to getting impression reporting based on anonymized IP addresses linked to impression delivery, such as on the Hulu app in a PlayStation device. Now, some major publishers – already wary of combining viewership and user data for privacy-related reasons – won’t share IP addresses tied to information about an ad exposure.

“We might see an IP address, but we don’t know which app or publisher actually ran [the ad],” said McCarver, who noted that there are even some publishers that don’t feel comfortable passing any IP address information at all, although they’re in the minority.

Because IP addresses are only available depending on the partner, McCarver said, agencies have to do “a lot of juggling” to piece together a cross-device campaign plan.

“Data transparency with IP addresses has gotten murkier,” he said.

Trying different ingredients

Still, the ad industry continues to work on workarounds.

For instance, many publishers are starting to package IP addresses with anonymized identifiers through a third party, such as TransUnion or Experian, to help ensure that targeting and attribution can still happen should privacy regulations further restrict the use of IP addresses.

For example, TransUnion creates IDs using hashed emails, home addresses and IP addresses. Experian takes a similar approach by using hashed emails, cookies and mobile ad IDs in addition to IP addresses to create its household identifiers.

If one signal is no longer available, it would still be possible to target and measure campaigns.

But for as long as they are available, IP addresses will remain the main ingredient in CTV’s ad targeting formula.

“IP addresses are still the most widely used identifier for connected TV, and will [continue] to be a mainstay,” said Julie Clark, SVP of diversified markets, media and entertainment at TransUnion.

Technically speaking

Even The Trade Desk’s Unified ID 2.0, which is based primarily on hashed email, uses IP addresses to tell which UIDs are connected to the same household, which helps with managing reach and frequency for TV ads, a company spokesperson told AdExchanger.

But buyers are also embracing third-party IDs for the sake of consistency.

Horizon Media uses its identity graph, which was built on top of TransUnion’s identity spine, to fill in gaps and inconsistencies in the data publishers share.

As an advertiser, “hopefully you have an ID that can span multiple devices” and link ad exposures with viewers, McCarver said.

And ad tech companies, too, have had to adapt to the growing publisher preference for third-party IDs.

In June, TV buying and measurement platform Tatari launched a sister company to house its new clean room, which matches first-party data from publishers and advertisers with Experian IDs to create unique identifiers that don’t rely on IP address.

Prior to that launch, Tatari was mostly dependent on IP addresses to track ad exposures, which remains the case today for many players in the industry.

Despite changes, challenges and potential regulatory scrutiny, IP addresses continue to be used heavily in CTV.

And although the TV industry may say it’s future-proofing for privacy, the process has created blaring inconsistencies in data sharing.

The next step is to bring order to the chaos.